- GreenMatch

- Blog

- Environmental Impact of Vinegar

Is Vinegar Bad For The Environment? Statistics, Trends, Facts & Quotes

Vinegar, an acetic acid solution, is a popular household product because of its versatility. It has various applications, from cleaning to cooking, and is praised for its natural and safe qualities, biodegradability, veganism, and non-toxicity. However, when evaluating whether vinegar is bad for the environment, there's more to the story than its green cleaning credentials.

This analysis explores the world of vinegar, including its production process, potential benefits and drawbacks, and overall impacts on our planet. We'll also explore statistics and trends to give you a well-rounded picture.

So, is that bottle of vinegar in your pantry an eco-friend or a hidden foe? Let's find out!

- What do we mean by vinegar exactly?

- Vinegar in the largest economies

- Environmental impact of vinegar

- Is vinegar sustainable?

- Is vinegar toxic?

- Can you recycle vinegar?

- Is vinegar biodegradable?

- Environmental impact of vinegar compared to everyday things

- Statistics, facts and figures about vinegar

- What are vinegar alternatives?

- FAQ

What do we mean by vinegar exactly?

Vinegar is a sour-tasting liquid produced primarily through alcohol oxidation in wine, cider, or other fermented substances. Vinegar has been used for centuries in food preservation, particularly in pickling processes, to extend the shelf life of perishable foods by killing bacteria.

Different types of vinegar include apple cider vinegar, balsamic vinegar, white distilled vinegar, and red or white vine vinegar.

It is mostly water, with around 4–5% of it being acetic acid, the clear, colourless liquid that gives vinegar its sour bite.

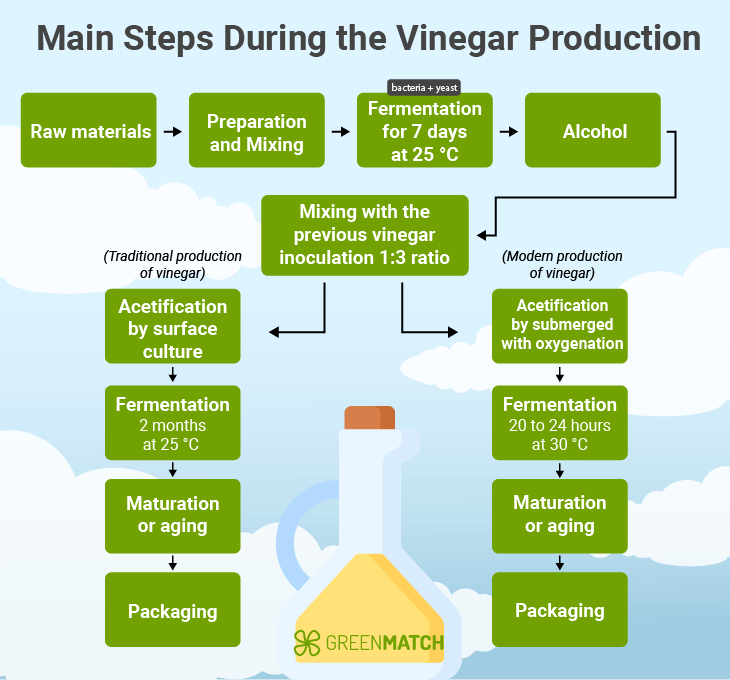

The oldest way to produce vinegar is through traditional fermentation. It uses naturally occurring bacteria (acetobacter) that convert alcohol (like ethanol from wine) into acetic acid at room temperature.

Nowadays, the global industrial demand for acetic acid is 6.5 million tonnes yearly. To satisfy such a tremendous demand, synthetic fermentation in vinegar production has taken the lead. It employs engineered microbes or enzymes specifically designed to convert specific sugars or starches directly into acetic acid. This method can be faster and more controlled than relying on naturally occurring bacteria.

Industrial vinegar production encompasses both synthetic and natural/fermentation-based methods. During this process, huge aluminium tanks transform wine into vinegar within 24 hours.

Vinegar in the largest economies

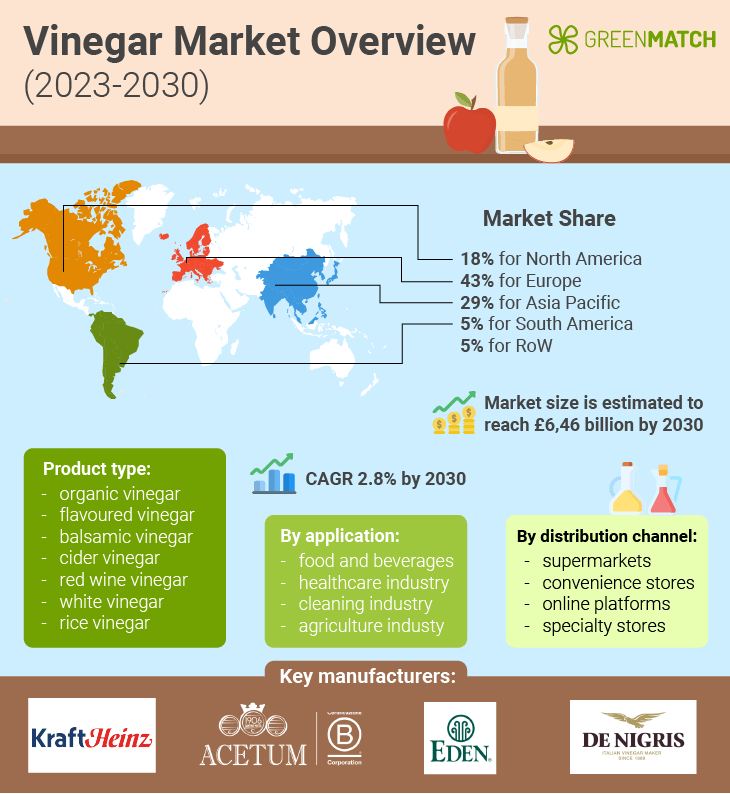

The global vinegar market is expected to grow significantly, with the global supply of vinegar projected to reach 816 million kilograms by 2026, up 1.9% year on year.

In terms of consumption, the European Union (EU) was the largest market for vinegar in 2018, with a market value of £648 million. The countries with the highest volumes of vinegar consumption in the EU were Germany (232 million litres), France (183 million litres), and Italy (119 million litres), together accounting for 49% of total consumption.

In 2018, the production of vinegar in the EU amounted to 1.2 billion litres, with Germany (211 million litres), Italy (185 million litres), and France (182 million litres) being the top three producers, accounting for 50% of total production.

In Asia, China is a significant vinegar consumer, with an annual consumption of approximately 4.6 million metric tons. The global vinegar market is also expected to grow due to increasing consumer preference for organic and natural foods and the versatile applications of vinegar in the food industry.

Environmental impact of vinegar

Is vinegar bad for the environment? Luckily for eco-enthusiasts, the answer is no. But there's a catch. Such eco-friendliness applies only to naturally fermented vinegar. And even with that, traditional vinegar production still leaves its carbon footprint.

A 2019 analysis using PCR found that the CO2 emissions of traditional balsamic vinegar range from 1.94 to 2.54 kg CO2 per litre. This analysis also considered its ecological footprint, which varies between 9.83 and 13.23 grams per square meter per kilogram. Its water footprint falls between 1332 and 1892 litres per litre.

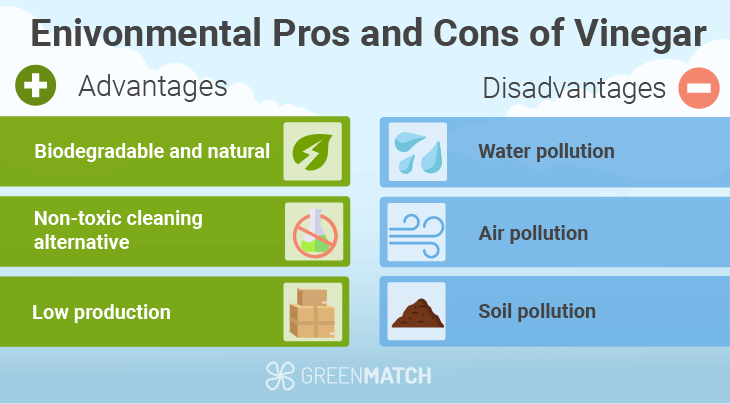

Generally, its natural origin, biodegradability, and low production footprint make naturally fermented vinegar a clear winner when considering its impact on the planet. And here's why:

- Biodegradable and natural: Vinegar is produced through a natural fermentation process using readily available materials like fruits or grains and alcoholic liquids like wine or cider with bacteria. This natural process makes it readily biodegradable by microorganisms, leaving behind no harmful residues.

- Non-toxic cleaning alternative: Compared to harsh chemical cleaners, vinegar is a safe and effective cleaning agent. It doesn't pollute waterways or introduce harmful toxins into the environment. Also, it is diluted with water, making it a budget-friendly option. Plus, any leftover cleaning solution can be rinsed away confidently, knowing it won't leave behind harmful residues.

- Low production footprint: Vinegar production typically uses agricultural products as base materials, and the fermentation process requires minimal energy input.

Yet it's worth noting that traditional fermented vinegar production is slow, usually taking anywhere from 2-3 weeks up to 1-3 months.

Traditional balsamic vinegar must be aged for at least 12 years!

Alternatively, synthetic vinegar offers a faster way to produce 15% and 20% vinegar in 24 and 60 hours, respectively.

What are the disadvantages of vinegar?

Synthetic vinegar production utilises a chemical reaction to create acetic acid directly from petrochemicals. This production method is also called imitation or artificial vinegar making.

Petrochemicals are derived from fossil fuels, and their use in vinegar production raises some environmental concerns:

- Water pollution: Extracting and transporting petrochemicals can disrupt ecosystems and potentially lead to oil spills, harming marine life and habitats. Such vinegar contaminates wastewater with sulfides and ammonia and disrupts the nitrogen cycle and pH balance in aquarium and pond systems, making it unsuitable for many aquatic species.

- Air pollution: Burning petrochemicals during production can produce smog and air pollution, emitting potential cancer-causing agents, carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxide, and hydrogen sulfide.

- Soil pollution: Vinegar can upset the soil's effectiveness by lowering its pH. This negatively impacts certain plants, like blueberries, raspberries, blackberries, or cranberries, which need very acidic soil conditions to grow.

As a rule, such industrial manufacturing methods are cheaper to run, affecting the final cost of vinegar.

The cost to produce one litre of synthetic vinegar is estimated to be around £1.60–£3.20. At the same time, the cost for traditional vinegar production ranges from £3.20–£9.60 per litre, with high-quality traditional vinegar potentially costing even more.

Therefore, the cheaper vinegar is, the less eco-friendly it is.

To conclude, traditionally, fermented vinegar is a much more environmentally friendly option than many conventional cleaning products. Opting for naturally fermented vinegar is a more costly option, yet it helps minimise its environmental footprint.

Is vinegar sustainable?

While the fermentation process behind vinegar production is microorganism-driven and doesn't directly create CO2 emissions (unlike fossil fuel-based processes), the chosen method hinges on its overall sustainability.

The traditional method (mainly the Orleans process) relies on natural fermentation, making it an environmentally friendly choice. It avoids synthetic or petrochemical processes often used in artificial vinegar production.

Synthetic vinegar production may have a larger carbon footprint due to its dependence on petrochemicals and fossil fuels.

The Orleans process is more artisanal and produces exceptional-quality vinegar due to the slow fermentation process and traditional ageing techniques.

Ways to make vinegar more sustainable

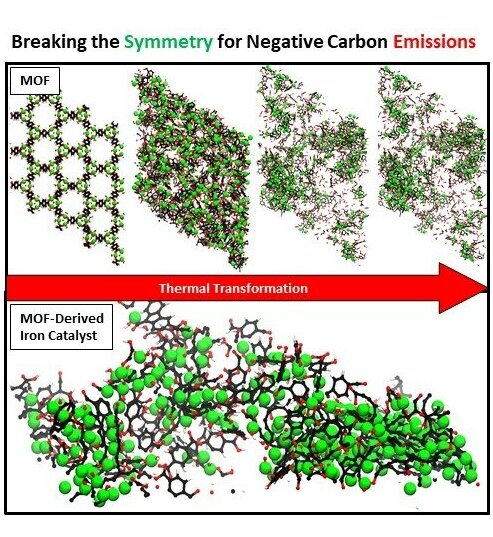

Developing new methods to produce acetic acid from captured CO2 could create negative carbon emissions and reduce the environmental impact of industrial vinegar production.

Chemical engineers at Monash University have developed an industrial process to produce acetic acid that uses the excess carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere and can potentially create negative carbon emissions. Their study, published in Nature Communications, describes a new catalyst using a special material called a metal-organic framework (MOF) containing iron. This catalyst helps convert captured carbon dioxide into acetic acid.

This method uses captured carbon dioxide to reduce pollution from manufacturing and reuse CO2, a greenhouse gas. It also has the potential to help slow climate change.

The study's leading investigator, Associate Professor Akshat Tanksale, says this research can encourage businesses to adopt the offered method.

“CO2 is over abundant in the atmosphere and the main cause of global warming and climate change. Even if we stopped all the industrial emissions today, we would continue to see negative impacts of global warming for at least a thousand years as nature slowly balances the excess CO2,” Associate Professor Tanksale stated.

Experts are enthusiastic about this discovery for both environmental and economic reasons. Researchers are already working with companies to bring this technology to market. As a consumer, consider the production process when selecting vinegar to make an eco-friendly choice. Look for brands that emphasise traditional fermentation methods.

Is vinegar toxic?

No, vinegar itself isn't toxic. It is a safe product for most household uses when consumed in diluted forms (4–7% acetic acid). However, it can be harmful in certain situations:

- Concentration: Undiluted or high-concentration vinegar can irritate or burn skin and eyes. Usually, in such cases, we're talking about vinegar that contains higher acetic acid concentrations, sometimes up to 98.6%. It is highly corrosive and causes severe irritation or burns to the skin, eyes, and digestive system.

- Ingestion: Ingesting large amounts of undiluted, high-concentration vinegar can lead to serious issues like ulcerative injury to the throat and oesophagus, nausea, vomiting, and even gastrointestinal bleeding. Children are especially at risk, as even small accidental ingestions of concentrated vinegar can be dangerous and potentially life-threatening.

- Inhalation: The strong, pungent fumes from highly concentrated vinegar can irritate the airways and mucous membranes, causing coughing, choking, and breathing difficulties. Prolonged exposure to the vapours may also lead to more severe respiratory issues.

Vinegar can be a part of a healthy diet, but only when consumed and used in moderation. Dilute vinegar before drinking by mixing 1 tsp to 2 tbsp of vinegar into a glass of water. Avoid mixing vinegar with bleach or other harsh chemicals for cleaning, as this can create toxic fumes.

Can you recycle vinegar?

Vinegar is a product you can use and reuse in various ways, but it is not typically recycled in the traditional sense, like plastic or glass. Once the vinegar is consumed, you can repurpose vinegar bottles or containers for other uses.

However, due to its acidity, improper disposal can harm the environment. You can safely neutralise small amounts by diluting it with water before pouring it down the drain.

Remember, you can (and need to) recycle the containers in which vinegar comes.

- If you rinse clean and dry, glass vinegar bottles are often recyclable in curbside programs. Check with your local recycling guidelines for specifics.

- Plastic vinegar bottles need to be recycled based on local rules. Look for the recycling symbol and number on the container to see if it's accepted in your area. Generally, #1 and #2 plastics (PET and HDPE) are commonly recyclable for beverage bottles and jugs.

Is vinegar biodegradable?

Yes, being mostly acetic acid and water, vinegar is biodegradable. Vinegar breaks down easily in the environment without causing harm, making it a sustainable and eco-friendly choice for cleaning and other applications.

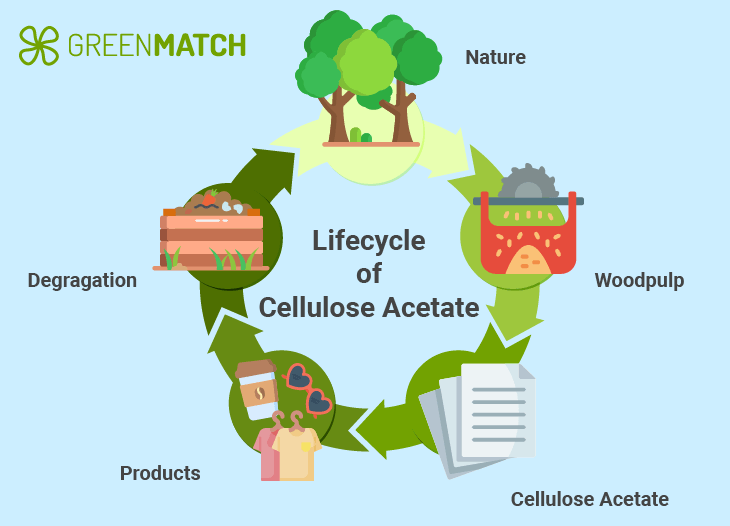

However, synthetic vinegar is generally less biodegradable due to its lack of natural fermentation and the petrochemicals used for manufacturing. In contrast, cellulose acetate, a material used in producing some types of vinegar, is biodegradable and can break down into cellulose and acetic acid that can be reabsorbed into the environment.

Environmental impact of vinegar compared to everyday things

As mentioned before, the carbon footprint of aged, traditionally fermented vinegar ranges from 1.94 to 2.54 kg CO2 per litre. Compare this to the environmental impact of its production and other everyday products:

- Textiles: the carbon footprint of textile production can vary widely, being 8.3kg CO2 for cotton, 13.89kg for wool, and 4.5kf for linen.

- Meat: Beef production has a very high carbon footprint, estimated at 27 kg CO2 per kg. Pork's carbon footprint is 12.1kg of CO2, chicken's is 6.9 kg, and lamb's is a whopping 39.2kg of CO2 per kilo.

- Paper bags: a recycled and lightweight paper bag makes 12g of CO2, and a paper bag from a clothing store has a CO2 footprint of 80g of CO2.

- Dairy: the carbon footprint of eggs is 4.8kg of CO2 per kg, cheese – 13.5kg of CO2 per kilo, and milk has the lowest CO2 footprint – 1.9kg of CO2.

Statistics, facts and figures about vinegar

- A tablespoon (15ml) of apple cider vinegar provides 3Kcal/13KJ, 0.1g carbohydrate, 11mg potassium, 1mg calcium, and 1mg magnesium. It doesn't contain many vitamins or minerals but does include some amino acids and antioxidants.

- Vinegar's acidic nature allows it to last indefinitely without refrigeration.

- The global vinegar market was valued at £5 billion in 2022 and is expected to expand at a CAGR of 2.8% from 2023 to 2030.

- Kraft Heinz Company (USA), Acetum (Italy), and Shanxi Shuita Vinegar (China) are the top three vinegar manufacturers worldwide.

- Synthetic vinegar accounts for around 57.7% of the global market revenue share.

What are vinegar alternatives?

When searching for vinegar alternatives, the best choice is to choose companies that produce naturally fermented vinegar made from fruits, grains, and alcoholic liquids.

If you prioritise convenience and portability or dislike vinegar's strong taste and smell, you could opt for dried or powdered vinegar. It is milder in flavour and you can easily add it to foods and seasonings. Moreover, powdered vinegar allows the vinegar flavour to be incorporated into dry, crispy foods without compromising the texture.

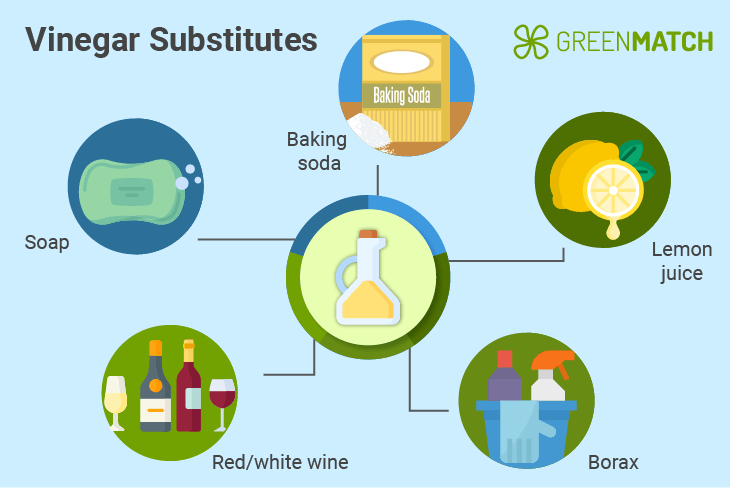

Yet, there are situations where a substitute might be necessary. Here are some alternatives to vinegar, depending on your needs:

Cooking substitutes:

- Lemon and lime juice: These citrus juices offer a similar acidity to vinegar and can be used in salad dressings, marinades, and sauces. However, they have a brighter, more citrusy flavour that may only sometimes be ideal.

- White and red wine: For certain recipes, like deglazing a pan, a splash of white or red wine can replace vinegar and add a subtle grapey flavour.

- Other acidic fruits: Cranberries, tamarind, and rhubarb can be used in small amounts to add tartness to dishes.

Cleaning substitutes:

- Baking soda: A natural cleaning agent, baking soda is excellent for scrubbing and absorbing odours. It's ineffective as a disinfectant but works well on ovens, sinks, and carpets.

- Castile soap: This gentle soap made from vegetable oils effectively cleans most surfaces. Dilute it with water for a sprayable solution.

- Borax: A mineral powder, borax can be used to clean grease, grime, and mildew. However, it can irritate the skin, so wear gloves when using it.

- Lemon juice: Lemon juice is a natural disinfectant you can use to clean cutting boards, countertops, and stainless steel appliances.

These alternatives may only sometimes be a perfect swap for vinegar, especially when it comes to pickling or preserving food. Vinegar's acidity plays a crucial role in these processes and you should only replace it with a proper recipe adjustment.

Is vinegar better than the alternatives?

While the alternatives mentioned above can sometimes substitute for vinegar in cooking and cleaning, they each have unique properties and may not always be a direct replacement. Here's a quick breakdown:

| Substitute | Type of vinegar substituted | Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|

| Lemon and lime juice | Apple cider vinegar, malt vinegar, white vinegar | Have a pH level of around 2–3, similar to vinegar (2–4). They have a distinct citrus flavour that may not always be desirable. Vinegar has a more neutral flavour profile |

| White and red wine | Apple cider vinegar, red wine vinegar, white wine vinegar, sherry vinegar | Its pH level is comparable to vinegar but its primary function is flavouring, not adding acidity |

| Baking soda | Distilled white vinegar | Excellent for scrubbing and deodorising; has a pH of 8-9 and neutralises acids, making it ineffective against some bacteria |

| Borax | Distilled white vinegar | Can irritate the skin so gloves are recommended |

| Castile soap | Distilled white vinegar | Perfect for gentle cleaning; lacks disinfecting properties |

When choosing an alternative, consider the desired outcome (acidity, cleaning power, flavour profile) to select the most suitable substitute.

FAQ

Yes and no. Traditionally, fermented vinegar made from natural sources like wine or fruit juices has a relatively low environmental impact. However, synthetic or petrochemical-based vinegar may have a higher carbon footprint and create more pollution.

Yes, acetic acid can be considered a petrochemical. Generally, it’s a natural product resulting from the fermentation of some foods, such as when wine or other alcoholic beverages become exposed to air. This converts the ethanol to acetic acid to produce vinegar. However, because acetic acid naturally occurs in small amounts, most global production happens through synthetic, petrochemical-based processes.

Several eco-friendly alternatives to using regular household vinegar include apple cider vinegar, baking soda, castile soap, hydrogen peroxide, or any cleaning products made with natural, plant-based ingredients instead of harsh chemicals.

We strive to connect our customers with the right product and supplier. Would you like to be part of GreenMatch?

- What do we mean by vinegar exactly?

- Vinegar in the largest economies

- Environmental impact of vinegar

- Is vinegar sustainable?

- Is vinegar toxic?

- Can you recycle vinegar?

- Is vinegar biodegradable?

- Environmental impact of vinegar compared to everyday things

- Statistics, facts and figures about vinegar

- What are vinegar alternatives?

- FAQ