- GreenMatch

- Blog

- Deep Sea Mining Statistics: Key Facts and Trends for 2025

Deep Sea Mining Statistics: Key Facts and Trends for 2025

Deep sea mining is gaining attention as a debated and potentially game-changing industry in the 21st century. This activity involves extracting minerals and metals from the seabed at depths exceeding 200 meters. It has sparked interest due to the growing need for metals crucial to modern technologies.

With land-based mineral reserves becoming scarcer and more complex to access, the abundant deposits of metals and minerals on the ocean floor have captured the interest of mining companies. These deep sea resources are estimated to be valued between £6.232 trillion and £12.46 trillion, encompassing metals like cobalt, nickel, copper, and manganese found in forms such as nodules, seafloor massive sulfides, and cobalt-rich crusts.

Moreover, the demand for metals such as nickel, cobalt, and manganese to make batteries, electric cars, and renewable energy systems fueled the increasing fascination with deep sea mining. Supporters believe deep sea mining might supply these resources, possibly aiding the shift towards a more environmentally friendly economy.

Understanding what deep-sea mining entails and its implications is crucial, as it intertwines with the broader narrative of marine conservation and sustainable resource utilisation.

This article explores the intricate world of deep-sea mining, elucidating its processes and potential impacts on marine biodiversity.

What is Deep Sea Mining?

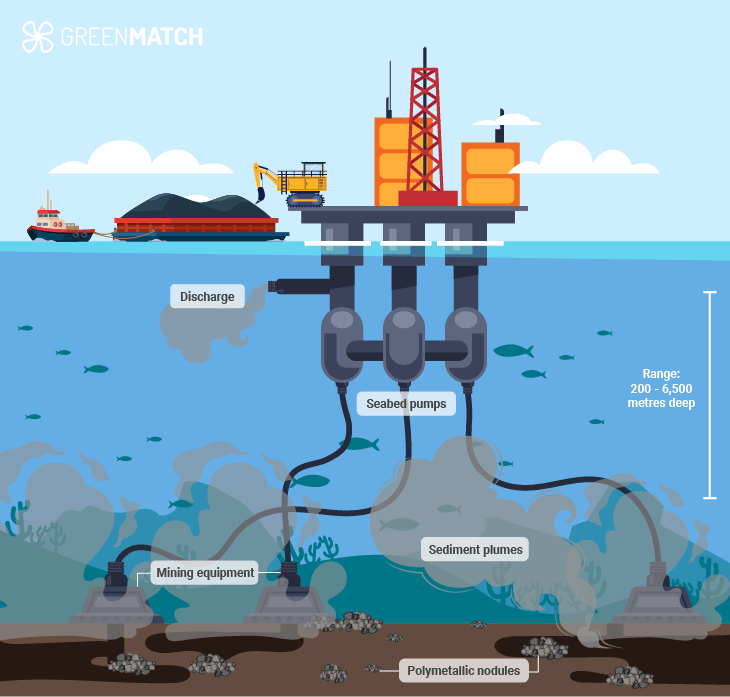

Deep sea mining involves extracting minerals and metals from the seabed, typically 200 to 6,500 meters deep. This practice targets deposits of manganese, nickel, cobalt, and rare earth elements crucial for modern technologies such as solar panels, rechargeable batteries and electronics.

Over millions of years, these resources form into polymetallic nodules, massive sulfides on the seafloor, and cobalt-rich crusts. This is characterised by removing these metal and mineral deposits from the ocean floor, where significant accumulations have developed into potato-sized nodules.

The extraction process involves large machines that collect these nodules or crusts and transport them to the surface for processing.

By 2030, it is projected that up to 10% of global production of minerals such as cobalt, copper, and zinc could be sourced from the ocean floor, potentially generating a global turnover of up to £8.441 billion. This significant shift towards deep-sea mining reflects the growing importance of underwater mineral resources in meeting the global demand for essential metals and minerals.

Please note: These prices, as of the time of publication, are subject to frequent fluctuations due to market conditions, global economic factors, and supply-demand dynamics.

The Allure of Underwater Riches

The deep seabed contains abundant deposits of valuable metals and minerals, including:

- Polymetallic nodules: Potato-sized rocks rich in manganese, nickel, copper, and cobalt

- Seafloor massive sulfides: Deposits near hydrothermal vents containing copper, gold, silver, and zinc

- Cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts: Layers on seamounts with high concentrations of cobalt, tellurium, and rare earth elements

Key Statistics, Facts and Trends for 2025

Deep-sea mining is a burgeoning industry that involves extracting minerals from the ocean floor. This practice poses significant environmental risks and has sparked global debate. These statistical facts and data were derived from Statista, IUCN, ISA, WWF, and other environmental studies.

Here are some key statistics and facts about deep-sea mining:

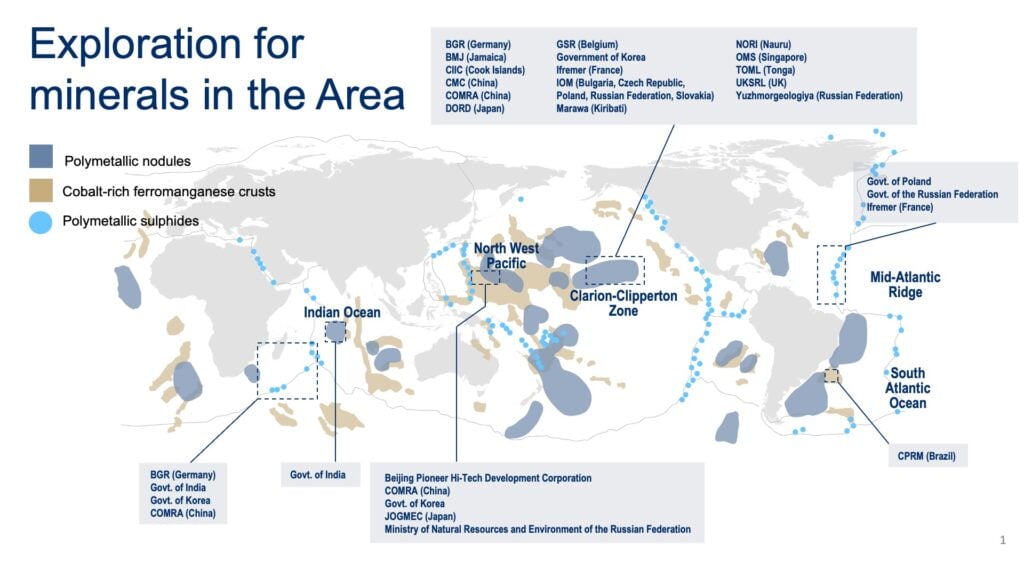

- Global Exploration Areas: As of 2019, significant land areas have been granted for deep-sea mining exploration.

- The International Seabed Authority (ISA) has issued 31 contracts for seabed mineral exploration, of which 30 are currently active.

- Contract Duration: Each contract lasts 15 years.

- China holds five active contracts for deep-sea mining exploration, the highest number globally.

- India recently applied for two new licenses, potentially bringing its total to four contracts.

- The International Seabed Authority (ISA) is still developing regulations for deep-sea mining, with guidelines expected to be established by 2025.

- The Clarion-Clipperton Zone is a polymetallic nodules hotspot targeted by 17 exploration contracts.

- India focuses on polymetallic sulfides and cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts in the Central Indian Ocean.

- Exploration activities target polymetallic sulfides along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge.

- Currently, about 85% of these materials come from Asia.

- Deep sea mining could provide a more stable supply, reducing dependency on politically volatile regions.

- Scientists estimate that deep-sea mining could cause a 50% reduction projected by 2050 the extinction of species living on or within the seabed.

- The deep sea acts as a significant carbon sink. Mining disrupts carbon-rich sediments, affecting the ocean's role in carbon cycling and storage.

- Analysts project the global deep sea mining market will reach £12.3 billion by 2030.

- Sediment plumes can spread over 100 km from mining sites

- Jobs created by the deep-sea mining industry are estimated at 15,000.

- Researchers estimate mining operations could disturb 8,000-9,000 square kilometres of seabed over a 30-year license period.

- Global demand for deep sea minerals continues to grow, driven by clean energy technologies and electronics.

- North America and Europe are expected to experience substantial development due to high technology adoption and the presence of major industry players.

- China leads with 161,211.2 square kilometres, followed by the United Kingdom with 133,285.6 square kilometres.

- Other major players include:

- South Korea: 122,100 sq km

- France: 100,000 sq km

- Russia: 87,600 sq km

- Germany: 85,150 sq km

- Norway: 200,000 sq km

Mineral Deposits

Scientists estimate the seafloor contains:

- 21 billion tonnes of manganese nodules

- 1 billion tonnes of cobalt-rich crusts

- 100 million tonnes of polymetallic sulfides

These deposits hold significant quantities of valuable metals:

- Manganese: 5.2 billion tonnes

- Nickel: 274 million tonnes

- Copper: 234 million tonnes

- Cobalt: 94 million tonnes

Projected Deep Sea Mineral Production

| Year | Copper (tonnes) | Nickel (tonnes) | Cobalt (tonnes) | Manganese (tonnes) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2027 | 356,400 | 444,600 | 61,200 | 9,200,000 |

| 2030 | 400,000 | 500,000 | 70,000 | 10,000,000 |

| 2035 | 450,000 | 550,000 | 80,000 | 11,000,000 |

| Region | Type of Mineral | Number of Contracts | Key Countries Involved |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pacific Ocean | Polymetallic Nodules | 17 | China, Japan, South Korea |

| Indian Ocean | Polymetallic Sulfides, Cobalt-rich Crusts | 7 | India, Germany, Russia |

| Atlantic Ocean | Polymetallic Sulfides | 5 | France, Brazil, Poland |

Environmental Impact of Deep Sea Mining

Deep sea mining poses significant environmental risks, including habitat destruction, sediment plumes, and the potential extinction of undiscovered species. Scientists warn that biodiversity loss would be inevitable and irreversible, disrupting Earth's largest carbon sink during a climate crisis.

A study in Japan revealed a 43% decline in fish and shrimp populations within a year of mining activities.

This controversial industry targets mineral-rich deposits on the ocean floor, but its consequences extend far beyond the immediate extraction sites.

| Impact | Description | Affected Area |

| Habitat removal | Removal of nodules changes sediment geochemistry and destroys habitats | Direct mining site |

| Sediment plumes | Dispersion of fine sediments affects species' mobility and visualisation | Surrounding areas |

| Water discharges | Release of toxic compounds and altered water temperatures | Ocean surface and midwater ecosystems |

| Noise pollution | Disrupts marine communication and affects sensitive species | Wide ocean areas |

| Light pollution | Disturb organisms adapted to darkness in the deep sea | Deep sea zones |

Scientists warn that biodiversity loss could be inevitable and irreversible.

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| Area affected per mining operation | 8,000-9,000 sq km |

| Sediment plume dispersion | 10-100 km |

| Degraded major marine ecosystems | 60% |

| Marine species at risk of extinction | 10% (1,550+ species) |

| Recovery time for mined areas | Decades to Centuries |

In addition, the deep sea acts as a significant carbon sink. Disturbing these areas could release stored carbon, exacerbating climate change. Sediment plumes from these activities may disperse 10-100 kilometres beyond mining sites, affecting vast swathes of ocean.

The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) reports that 60% of major marine ecosystems in the sunlight zone have already degraded. It threatens to worsen this situation, potentially pushing fragile ecosystems past their tipping points.

Nearly 10% of assessed marine species with over 1,55o face extinction risks. This number could significantly increase, impacting unique deep-sea organisms.

What is the impact of deep-sea mining?

Total Impact per Year

Deep-sea mining could devastate approximately 8,000 to 9,000 square kilometres of the seabed over a 30-year license period. This equates to an annual impact of around 267 to 300 square kilometres. The loss of biodiversity and ecosystem services in these areas would be irreversible.

Impact per Day

Deep-sea mining could affect about 0.73 to 0.82 square kilometres of seabed daily. This continuous disturbance would lead to the gradual degradation of marine habitats, with long-term consequences for ocean health.

Impact per Usage

Each mining operation involves removing the top 6-20 centimetres of seafloor sediment, which could lead to the potential extinction of species living on or within it. The polymetallic nodules and other minerals targeted by mining support complex ecosystems that would be entirely lost.

The deep sea plays a crucial role in carbon sequestration. Mining disrupts this process, potentially reducing the ocean's ability to mitigate global warming. Additionally, these mining activities emit greenhouse gases, contributing to climate change.

Current State of Deep Sea Mining

The International Seabed Authority (ISA) has issued 31 exploration contracts covering over 1.5 million square kilometres of international seabed.

Leading countries include China, France, Germany, and Russia. Companies like The Metals Company and GSR are leading the way in developing mining technologies and conducting environmental assessments.

Top Economies Contributing to Deep Sea Mining

Countries and corporations justify it is necessary for the production of green technology. However, environmental concerns have prompted calls for moratoriums. The ISA faces pressure to finalise regulations as exploration activities intensify.

Some major economies are vying for control of valuable seabed resources. China leads the race, holding five exploration contracts with the International Seabed Authority (ISA). India follows closely with four contracts, while other nations like Japan, South Korea, and Russia actively pursue deep sea mining opportunities.

Top 8 Countries with ISA Exploration Contracts

| Country | Number of Contracts | Minerals Targeted |

|---|---|---|

| China | 5 | Polymetallic Nodules, Polymetallic Sulfides |

| India | 4 (pending approval) | Polymetallic Nodules, Polymetallic Sulfides |

| Russia | 3 | Polymetallic Nodules, Polymetallic Sulfides |

| South Korea | 3 | Polymetallic Nodules |

| UK | 2 | Polymetallic Nodules |

| Japan | 2 | Polymetallic Nodules |

| France | 2 | Polymetallic Nodules |

| Germany | 2 | Polymetallic Nodules |

These nations actively pursue valuable seabed resources, driven by the growing demand for minerals crucial to green technology production. However, environmental concerns cast a shadow over these endeavours.

Image credit: IUCN

Key Players and Strategies

The deep sea mining industry features a dynamic mix of established and emerging players, each employing unique strategies to secure critical mineral resources. As the global demand for critical minerals intensifies, these key players will shape the future of deep sea mining, balancing economic interests with environmental sustainability.

China continues to dominate the deep sea mining landscape, leveraging state-backed entities to secure multiple exploration licenses. However, several Western companies and emerging players are also making significant strides in this sector.

Chinese Dominance:

China Ocean Mineral Resources Research and Development Association (COMRA) holds the most exploration contracts with the International Seabed Authority (ISA), cementing China's leading position. The Chinese government has prioritised deep sea mining, investing heavily in technology development and exploration activities.

Western Companies:

- The Metals Company (TMC): Formerly known as DeepGreen Metals, TMC is a frontrunner in developing nodule collection technology. They have reported encouraging results from their NORI-D collector test and aim to start harvesting in the Clarion Clipperton Zone (CCZ) as early as 2025.

- Global Sea Mineral Resources (GSR): A subsidiary of the Belgian DEME Group, GSR holds licenses in the CCZ and continues to advance its baseline surveying and collector testing. They benefit from the backing of an experienced offshore operator.

Emerging Players:

- Loke Marine Minerals: This Norwegian company has quickly established itself as a formidable force in deep sea mining. In 2023, Loke acquired UK Seabed Resources' licenses in the CCZ, significantly expanding its portfolio. They have also attracted investments from major maritime and subsea industry players.

- Transocean: The world's largest operator of deepwater drilling platforms entered the deep sea mining scene in 2023. Transocean has made strategic investments, including contributing a drillship to GSR for exploration work and system integration testing.

Key Strategies:

- Technology Development: Companies invest heavily in developing environmentally friendly nodule collection technologies. For instance, GSR plans to conduct a full-scale system integration test in 2025.

- Strategic Partnerships: Many players are forming alliances to combine expertise. Transocean's partnership with GSR exemplifies this approach, merging offshore drilling experience with deep sea mineral exploration knowledge.

- Diversification: Some companies, like Loke Marine Minerals, pursue licenses in multiple jurisdictions to spread risk and maximise opportunities.

- Environmental Focus: With growing concerns about the environmental impact of deep-sea mining, companies are emphasising their commitment to sustainable practices and comprehensive environmental assessments

Key Locations and Projects

By understanding the key locations and projects, we can better appreciate the global implications of deep-sea mining and the urgent need for comprehensive regulations.

Prominent projects include:

- Cook Islands Seabed Minerals: Cook Sea Resources (CSR) holds licenses in the Cook Islands Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), boasting high-grade polymetallic nodule deposits exceeding 50 kg/m² in some areas. Full-scale production aims to commence around 2027/28.

- Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ): The Metals Company (TMC) leads exploration here, with plans to start harvesting as early as 2025. Global Sea Mineral Resources (GSR) also holds promising regional licenses.

- Norwegian Continental Shelf: Adepth Minerals focuses on surveying and data analysis for deep sea mining operations in Norway's EEZ.

- Bothnian Bay: Scandinavian Ocean Minerals explores polymetallic nodule deposits between Sweden and Finland, bringing deep sea mining closer to Europe's heart.

- Japan's Takuyo-Daigo Seamount: This site of a successful cobalt crust extraction in 2020 provides valuable data on environmental impacts.

| Location | Key Minerals | Environmental Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Clarion-Clipperton Zone | Manganese, Nickel, Cobalt | Species extinction, ecosystem disruption |

| Cook Islands EEZ | Polymetallic Nodules | Habitat destruction, biodiversity loss |

| Norwegian Seabed | Cobalt, Nickel, Copper | Ecosystem disturbance, sediment pollution |

| Takuyo-Daigo Seamount | Cobalt-rich Crusts | Decline in marine populations, sediment plumes |

Regulatory Framework

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and the International Seabed Authority (ISA) regulate these activities in pivotal ways.

The 1982 UNCLOS declared the seabed beyond national jurisdiction as the "common heritage of mankind." This means that all mineral exploration and exploitation activities must benefit humanity. The ISA, established under UNCLOS, oversees these activities, ensuring they comply with international regulations.

Key Provisions of UNCLOS

- Common Heritage Principle: All rights to resources in the seabed are vested in mankind.

- State Sponsorship: Activities must be sponsored by a State Party to UNCLOS.

- Environmental Protection: States must ensure effective control over activities to prevent environmental harm.

- Equitable Sharing: Financial and economic benefits from mining must be shared equitably.

National Regulations

Regulations vary significantly between countries. For instance, Norway has approved deep-sea mining exploration within its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), while the Cook Islands have granted exploration permits but not extraction permits. The United States is considering the Responsible Use of Seafloor Resources Act to regulate mining activities.

Internationally, the ISA requires contractors to comply with multiple regulatory frameworks, including sponsorship agreements and national laws of the sponsoring state.

However, there are concerns about the adequacy of these regulations to protect marine ecosystems, and several governments and organisations advocate for a moratorium on deep sea mining until robust environmental regulations are established.

Recent Changes and Developments

Recent developments highlight a growing international focus on the environmental impacts of deep-sea mining. The UK, for instance, has supported a moratorium on new deep-sea mining licenses pending further environmental studies and the ISA's development of robust regulatory frameworks.

Similarly, the ISA has been working towards establishing exploitation regulations, with a projected completion by 2025. This initiative follows significant debates and demands for stringent oversight to prevent potential environmental disasters

Economic Potential

Deep-sea mining presents a compelling economic opportunity, with the potential to unlock vast mineral wealth from the ocean floor. Estimates suggest that the value of gold in international seabeds alone could reach £150 trillion.

This immense economic potential stems from the abundance of polymetallic nodules, cobalt-rich crusts, and hydrothermal vents containing essential metals like nickel, manganese, cobalt, and copper. For instance, a single wind turbine requires 500kg of nickel, while electric vehicles demand triple the copper of conventional cars.

Economic Benefits

- High Returns: The estimated value of seabed minerals, particularly gold, highlights the high potential returns from deep-sea mining. This could significantly boost the global economy, particularly for countries with exclusive economic zones (EEZs) rich in these resources.

- Green Technology: Metals extracted from the seabed are crucial for green technologies. Deep-sea mining is pivotal for the transition to renewable energy sources.

- Job Creation: The development of deep-sea mining could create numerous jobs in engineering, marine biology, and related fields, particularly in developing nations with rich marine resources.

Economic Challenges

- High Costs: Deep-sea mining involves significant financial investment due to the untested and high-risk nature of the technology. The costs associated with developing and deploying the necessary equipment can be prohibitive.

- Uncertain Profitability: Despite the high potential returns, the profitability of deep-sea mining still needs to be determined. The technology is largely untested, and the environmental risks could lead to unforeseen expenses and regulatory hurdles.

- Environmental Liabilities: Companies involved in deep-sea mining face potential environmental liabilities. The destruction of marine habitats and biodiversity loss could result in substantial costs, both financially and reputationally.

Comparing Deep Sea Mining with Terrestrial Mining

While deep sea mining shows promise in reducing certain environmental impacts, scientists stress the need for further research before commercial exploitation begins.

| Impact Category | Deep Sea Mining | Terrestrial Mining |

|---|---|---|

| Ore Grade (Nickel) | 1.3% | 0.2% (avg. new mines) |

| Carbon Disturbance | 172.5 tonnes/km2/year | Varies by location |

| Habitat Destruction | Localised seabed disturbance | Extensive land clearing |

| Water Pollution | Sediment plumes | Acid mine drainage |

| Waste Generation | 99% usability rate | Large tailings volumes |

| Air Pollution | Minimal | Significant dust and emissions |

| Waste Management | Limited on-site waste (up to 99% usability rate) | Large tailings volumes and waste rock |

| Greenhouse Gas Emissions | Lower (estimates vary) | 4-7% of global emissions |

| Biodiversity Impact | High risk to unique ecosystems | Severe local ecosystem disruption |

| Social Impact | Minimal direct community impact | Potential displacement, health risks |

| Economic Potential | £780 billion annually (estimated) | £500 billion annually (estimated) |

| Regulatory Framework | Developing (ISA regulations by 2025) | Established but varies by country |

Future Prospects and Innovations

This deep-sea mining exploration has illuminated the complexities and pivotal considerations that frame this frontier industry. We parsed through the mechanisms of mining in oceanic depths, the intricate dance of economic gain against environmental stewardship, and the ongoing dialogue surrounding regulatory frameworks.

The deep sea remains one of Earth's least explored frontiers. Scientists have identified over 5,000 new species in areas targeted for mining, highlighting the rich biodiversity that could be at risk. The long-term impacts of mining on these ecosystems still need to be fully understood, necessitating further research and a cautious approach.

Countries like Norway are leading the charge in exploring deep-sea mining within their territorial waters. However, international treaties like the High Seas Treaty aim to protect oceanic biodiversity, potentially imposing stricter regulations on mining activities. The global community remains divided on whether the benefits of deep-sea mining outweigh the environmental costs.

In addition, several governments and organisations advocate for a moratorium on deep-sea mining until robust environmental regulations are established. Notable supporters include Germany, Spain, the UK, and global brands like Samsung and BMW.

Innovations in deep sea mining technology could reshape job markets. Projections estimate industry growth from £510 million in 2020 to £11.8 billion by 2030. This expansion demands specialised roles like ROV operators, environmental scientists, and robotics engineers.

Alternatives to deep-sea mining exist. Recycling initiatives, technological innovations reducing metal dependence, and recovery from mining waste offer promising avenues. These options align with circular economy principles and minimise reliance on virgin material extraction.

FAQs: Deep Sea Mining

Yes, deep-sea mining poses severe environmental risks, including irreversible ecosystem and habitat loss, potential extinction of unique species, and disruption of carbon storage, which could exacerbate climate change.

Deep-sea mining could become a significant industry due to the increasing demand for minerals like cobalt, nickel, and manganese. These minerals are essential for renewable energy technologies, such as batteries for electric vehicles and solar panels. However, scientists warn of potentially irreversible damage to marine ecosystems. The International Seabed Authority aims to finalise regulations by July 2025, with potential mining starting as early as 2025.

The ethics of deep-sea mining are hotly debated. Experts argue that it provides essential resources for technological advancement and the green energy transition. Critics, however, highlight significant environmental and ethical concerns. Deep-sea mining could damage marine ecosystems, cause biodiversity loss, and cause carbon storage disruption on the ocean floor. Ethical considerations include the lack of comprehensive scientific understanding and the potential for short-term economic gains to outweigh long-term environmental impacts.

Deep-sea mining has yet to commence on a commercial scale. The ISA continues to develop regulations and will finalise them by July 2025. Some companies, like The Metals Company, plan to start mining as early as 2025, pending regulatory approval. Meanwhile, countries like Norway and Japan are exploring the possibility of mining within their territorial waters. Despite these developments, significant opposition exists, with 25 countries calling for a moratorium or ban on deep-sea mining.

Inemesit is a seasoned content writer with 9 years of experience in B2B and B2C. Her expertise in sustainability and green technologies guides readers towards eco-friendly choices, significantly contributing to the field of renewable energy and environmental sustainability.

We strive to connect our customers with the right product and supplier. Would you like to be part of GreenMatch?