- GreenMatch

- Blog

- Is Fast Fashion Bad For The Environment?

Is Fast Fashion Bad For The Environment?

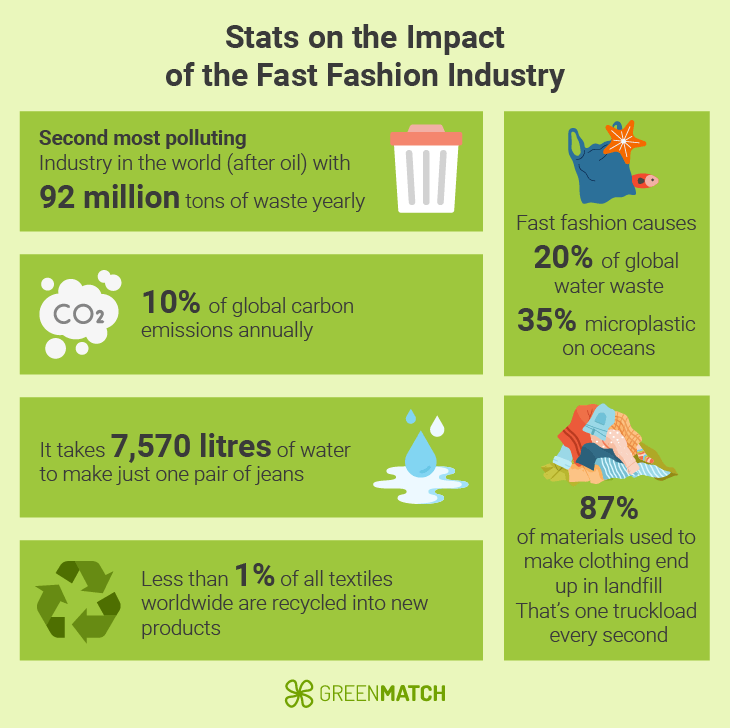

- The fast fashion industry is responsible for about 92 million tons of waste per year.

- Over 60% of fabrics used in fast fashion are nylon and polyester, which are non-biodegradable and make 35% of microplastic pollution in oceans.

- As of 2024, an average American buys around 68 pieces of clothing per year, as opposed to 12 pieces in the 1980s.

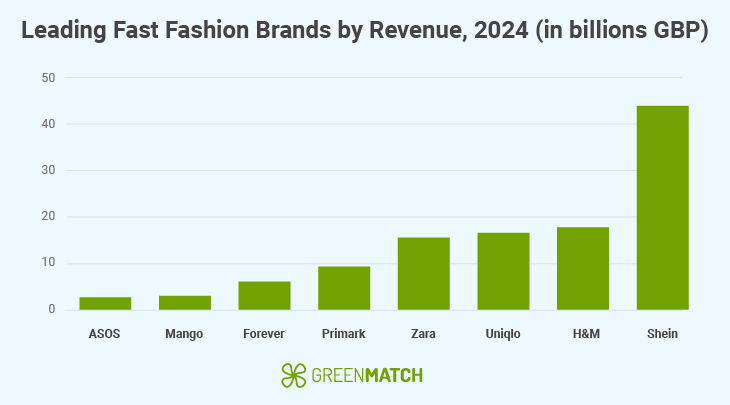

- The United Kingdom leads the European fast fashion market with £57.53 billion in revenue, followed by Germany with £48.42 billion.

Have you ever wondered why the clothes sold today just don't last or fit properly? Or why does that shirt from your grandpa's wardrobe still feel superior decades after it was made? And these are not some nostalgic observations; they actually represent the outcome of the modern fast fashion business model.

Fast fashion isn't just about quickly catching up with trends and following low manufacturing standards. It nurtures the throwaway culture, which in turn contributes to overconsumption: over the past 15 years, the number of times a clothing item is worn before its disposal dropped by 36%.

Sadly, fast fashion and throwaway culture have staggering environmental consequences, too. Only in the UK, around 350,000 tons of waste clothing end up in landfills every year.

Thus, the question of whether fast fashion is bad for the environment is rhetorical. However, in this piece, apart from taking a closer look at the scope of the environmental damage, we'll try to find out what there is to be done to revert this unsustainable trend.

What is fast fashion?

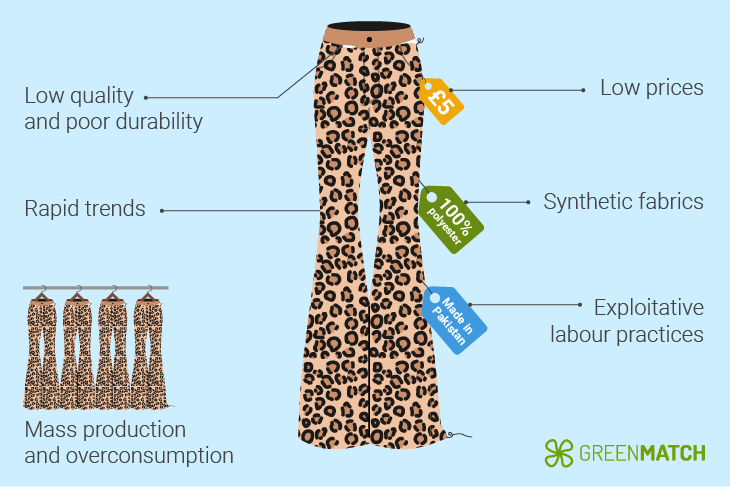

Fast fashion is a clothing production model that focuses on the rapid production of trendy, affordable clothing. It prioritises short product lifecycles to encourage quick garment disposal and frequent replacement.

As of 2024, the global fast fashion industry is valued at £106 billion, which is 10.74% higher compared to £94.44 billion in 2023. By 2032, the industry is expected to reach £228.22 billion.

While the fast fashion phenomenon appeared in the '90s, there were a number of cultural, technological and economic changes outside the fashion industry leading to its rise. Here are some key developments:

- Mass production capabilities: Between the 18th and 19th centuries, the invention of a roller spinning machine, power loom, and sewing machine increased production capacity, lowered garment costs, and allowed manufacturers to meet the growing demand for clothing.

- Standardisation of sizes: Between the 1930s and 1950s, a number of studies were conducted in the US and Europe to create the standardised 8 to 42 sizing system. Although later abandoned, this system laid the groundwork for creating clothing that fit a wider range of body types and kicked off mass production later on.

- The rise of consumer culture: In the 1960s and 1970s, many Western countries experienced considerable economic growth, which allowed consumers to spend more on non-essential goods like clothing. In addition, advances in synthetic fabrics, particularly polyester, aka a "miracle fibre," were cheaper to produce than natural fibres. At the time, consumers were unaware of polyester's environmental impact, and it was widely accepted by the middle classes.

- Globalisation and outsourcing: In 1994, US President Bill Clinton signed the NAFTA – North American Free Trade Agreement – which allowed for cheaper manufacturing in Mexico. In 2000, he granted Permanent Normal Trade Relations (PNTR) to China. Following this, big fashion brands relocated their production facilities to China and other countries with lower labour costs, such as Vietnam, India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. Thanks to these processes (is it thanks to though?), we spend only 3% of our income on clothing nowadays, as opposed to 7% in the 1980s. This means we're able to buy five times more clothing while paying less than consumers from three decades ago.

- The digital age: With the rise of the Internet and social media, consumers were able to see and share fashion trends in real-time. For example, SHEIN developed the data-first approach. They were the first to fast follow and analyse haute couture, street style, and celebrity fashion trends quickly through digital channels, react to demand in no time, and spread their cheap new-ins through influencers. While SHEIN's environmental impact is disastrous, its data-first approach is now copied by most fast-fashion bands.

- Marketing: In 1986, the term "retail therapy" was coined to market shopping as a form of emotional self-care. Moreover, frequent and almost rapid collection updates of key fast-fashion players and dirt-cheap replicas on marketplaces like SHEIN and Temu have introduced a "buy more, buy often" mentality, shifting the focus from quality to quantity and speed. This normalised disposable fashion has put a question mark on SHEIN's and Temu's sustainability.

These factors fundamentally transformed the fashion industry and made fashion more accessible worldwide. However, they also caused significant sustainability challenges that pose staggering environmental changes.

Environmental impact of fast fashion

Greenhouse gas emissions

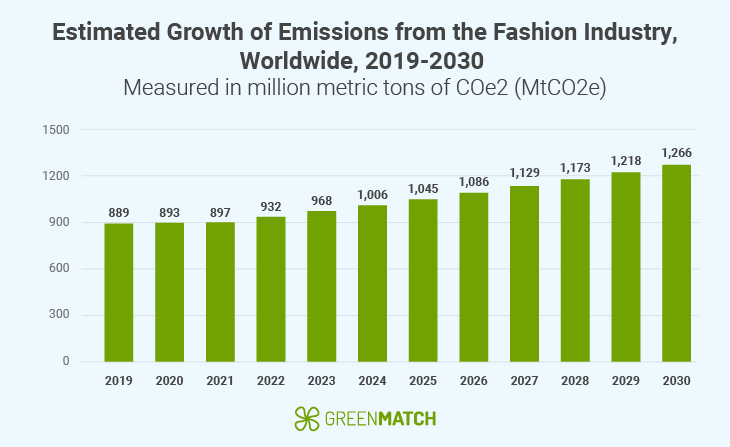

The fashion industry is accountable for 10% of global carbon emissions, producing 1.2 billion tons of carbon dioxide annually. This is higher than emissions coming from international aviation and maritime shipping together.

This is mainly due to resource-intensive processes, reliance on synthetic materials, and overproduction. Dyeing and finishing are responsible for 36% of the industry's greenhouse emissions, and yarn preparation accounts for 28%.

Since the top fast fashion brands locate their facilities in countries with limited renewable energy infrastructure, fossil fuel-dependent manufacturing processes continue to drive these figures up.

If current trends persist, the fashion industry could account for 26% of the world's carbon emissions in 2025.

Waste generation

It's a new cold reality: typically, clothing items are worn between 7 and 10 times before being discarded. On top of that, one in three young women labels clothes as "old" after being worn once or twice!

In 2022, returns tech platform Optoro estimated a staggering 9.5 billion pounds (4.3 billion kg) of returned clothes ended up in landfills, the weight equivalent to 10,500 fully loaded Boeing 747s.

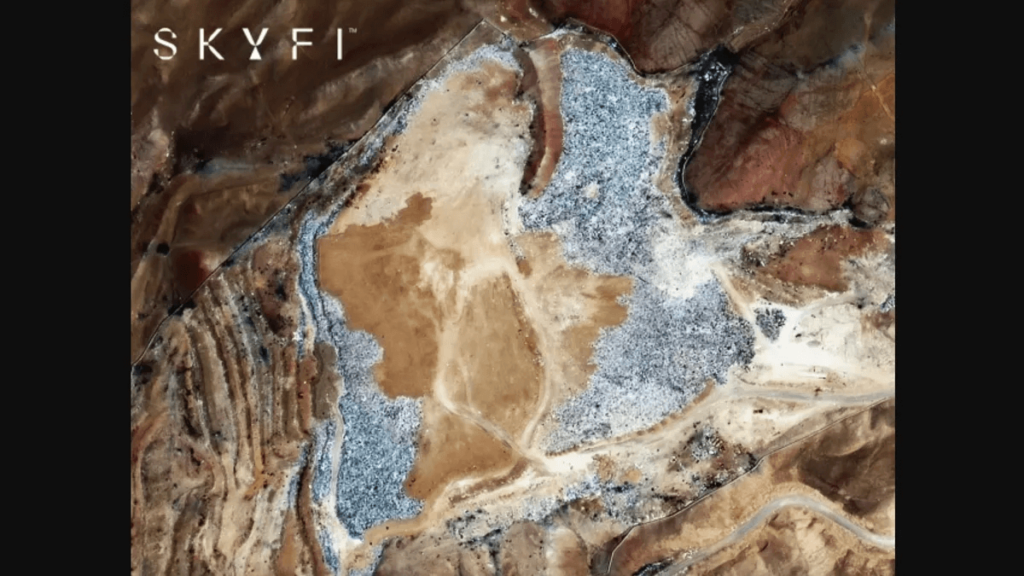

With 92 million tons of clothes thrown away each year, the world's textile waste generation problem has reached a point where it is visible from space.

In 2023, SkyFi published satellite photos of a mountain in the Atacama desert of northern Chile piled up with discarded clothes. The clothes were reportedly manufactured in China and Bangladesh and then failed to be sold in the American, European and Asian markets.

This garment pile is reportedly growing by around 39,000 tons per annum, coming mainly through the port of Iquique in the north of Chile.

Such wasteful practices contribute to a substantial economic loss of $500 (£391) billion annually, mainly because the discarded clothes are underused and under-recycled. The main challenge with recycling lies in the clothing's intricate material composition, often blending natural and synthetic fibres, plastic, and metals.

To tackle this issue, circular fashion economy programs like State of Matter's 360° AFTERLIFE PROGRAM, SuperCircle, Tracing Textile Waste Project, T-REX Project and many others have been introduced. The programs consist of a take-back system, upcycling, recycling, reselling, and refurbishing garments.

They aim to improve transparency in the certified supply chain and textile-to-textile recycling, demonstrate the full recycling process for various materials, and streamline closed-loop textile recycling through digital tools.

Water consumption and pollution

Cotton is one of the primary materials used in fast fashion manufacturing. Producing a single cotton T-shirt and a pair of jeans requires 2,706 and 7,570 litres of water, respectively. This excessive water consumption highlights the serious environmental impact of cotton, raising questions about its sustainability.

Polyester, another major fabric used in fast fashion manufacturing, has a large grey water footprint because it cannot be dyed naturally and requires chemical dyes. Polyester clothes shed around 124-308 milligrams of microfibres per kilogram, with 40-60% of microplastics emitted with the first wash.

Because of this, synthetic fibres like polyester are responsible for 35% of global microplastic pollution in oceans.

Dyeing and finishing processes, which are inseparable parts of clothing production, also require significant water resources.

Generally speaking, the textile sector consumes around 1.5 trillion litres of freshwater across its entire value chain globally. Such high water consumption is extremely problematic for countries with already scarce water resources, such as Bangladesh, Cambodia, India, Pakistan, and Vietnam.

Since these are also the top locations for fast fashion production, high water consumption is particularly concerning there:

- Bangladesh factories consume around 250-300 litres of water per kilogram of fabric produced, which exceeds global benchmarks (81.8 litres as a standard).

- In India, for every 1kg of cotton produced, 22,500 litres of water is consumed. With around 70% of untreated industrial waste being disposed into water bodies, the Yamuna River receives about 500 million litres of wastewater daily.

- The textile industry in Pakistan uses up to 90 million acre-feet of water yearly, which is 45% of the country's total freshwater usage.

- In Vietnam, only 1% of wastewater treatment comes from the textile sector. Wet fabric processing factories generate wastewater containing formaldehyde, chlorine, azo dyes, and other chemicals, along with untreated effluents, which greatly affect the health of people populating the surrounding areas.

- In Cambodia, the garment industry accounts for 69% of all toxic discharges, releasing industrial wastewater in landfills. Due to the informal reuse of waste garments being burned in brick kilns, additional pollutants are released into the environment.

With major brands like Zara, H&M, Primark, Uniqlo, Mango, and others locating production facilities or outsourcing to low-cost suppliers in these countries, the water pollution problem will continue to exacerbate there.

China, the world's largest textile producer, also faces similar challenges. While producing 65% of clothing in the world, it's responsible for 20% of global industrial water pollution.

To tackle this issue, the Chinese government implemented the "Water Pollution Prevention and Control Action Plan" (aka Water Ten Plan) in 2015. The plan focused on waterless dyeing processes and a closed-loop water recycling system.

These measures boosted the water recycling rate from 15% to 30% and reduced the wastewater and pollutants discharge by over 10%.

Chemical usage

Did you know that around 8,000 different chemicals are involved in clothing production? The most common chemicals are:

| Chemical Name | Process Used For | Health Impacts |

|---|---|---|

| Glyphosate | Cultivation of genetically modified cotton | Respiratory issues, skin irritation, a probable carcinogen |

| Phthalates | Used as plasticisers in faux leather, raincoats, and plastisol prints | Endocrine disruption, reproductive issues, early puberty, increased risks of obesity and diabetes, some phthalates are linked to cancer |

| Azo dyes | Dyeing textiles, especially polyester | Skin irritation, allergic reactions, carcinogenic effects due to aromatic amines |

| Formaldehyde | Fabric finishing for wrinkle resistance and durability | Respiratory issues, skin irritation, probable human carcinogen linked to nasopharyngeal cancer and leukemia |

| PFAS | Waterproofing, stain resistance, and thermal stability in textiles | increased risk of certain cancers, developmental issues, immune system suppression |

| Lead | Dyeing process | Can damage the brain, heart, kidneys, and reproductive systems. |

| Chromium | Dyeing and leather treatment | Weakens immune system, potential carcinogen |

| Cadmium | Dyeing | Cadmium exposure can lead to kidney damage, lung damage, gastrointestinal issues, and is classified as a human carcinogen. |

| Antimony | Dyeing of polyester textiles | Potentially carcinogenic, causes respiratory issues, skin irritation, gastrointestinal symptoms |

| Chlorine bleach | Bleaching denim | causes respiratory issues, skin irritation, potential chronic lung disease, and increased cancer risk |

These substances are called "forever chemicals" as they don't break down and threaten ecosystems. Heavy metals like lead, chromium, and antimony accumulate in ecosystems and enter the food chain, affecting wildlife and human health. They have been found to cause hormone disruption, cancer, respiratory irritation, liver damage and other health issues.

Sadly, these chemicals affect not only the planet but also workers and consumers. Chemical exposure is accountable for 50% of occupational diseases affecting garment workers. Consumers are also at risk as the end product can still contain residual chemicals.

In 2024, Seoul's government discovered that SHEIN, TEMU, and AliExpress were selling clothing with dangerous chemical levels. For example, a shocking discovery revealed that a pair of SHEIN shoes contained phthalates at a staggering 428 times the permissible level.

To address this, the Zero Discharge of Hazardous Chemicals (ZDHC) program was started in 2011 in response to the "Detox My Fashion" campaign by Greenpeace. This program involves 30 brands, 101 value chain affiliates, and 19 associates. It aims to shift the focus from end-of-pipe to beginning-of-pipe chemical management.

The Chemicals to Zero (CtZ) Programme was launched to categorise chemicals as "foundational," "progressive," and "aspirational." Its Manufacturers Restricted Substances List (MRSL) sets limits to certain substances in chemical formulations and targets 70% industry-wise conformance by 2030.

Environmental degradation

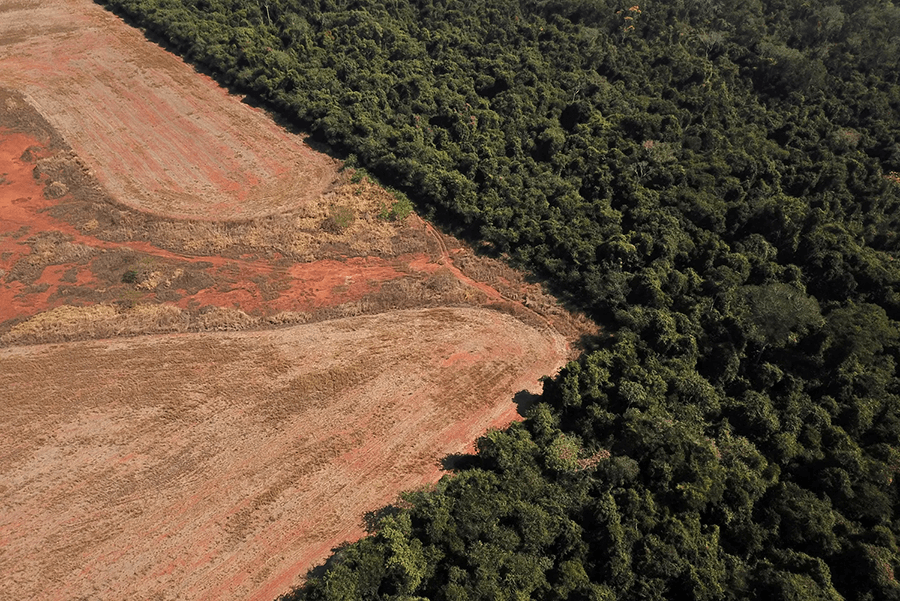

According to the non-profit Canopy, over 300 million trees are cut down every year to be further transformed into viscose, modal, lyocell and rayon.

While not being heavily discussed in the media, the supply chains of 48% of fast fashion brands are linked to deforestation, often times illegal.

The Cerrado, Brazil's vital ecosystem, has reportedly lost half of its vegetation due to extensive agriculture, especially cotton farming. 800,000 tons of tainted cotton have been traced to 8 clothing manufacturers in Asia supplying Zara and H&M, Earthsight claims.

If you have cotton clothes, towels or bed sheets from H&M or Zara, they may well be stained by the plundering of the Cerrado. These firms talk about good practice, social responsibility and certification schemes, they claim to invest in traceability and sustainability, but all this now looks about as fake as their highstreet window arrangements. - Earthsight director Sam Lawson

Because of this, brands like H&M, Zara, Allbirds, Uniqlo, SHEIN, and Nike have been accused of greenwashing. They all allegedly launched their eco-friendly collections while engaging in unsustainable practices.

For example, despite launching its garment recycling “Conscious” program, H&M faced backlash for including 100% polyester products in its collection. The company also allegedly provided misleading environmental information by using the Higg Index to rate their clothes as sustainable when, in fact, that was not true. H&M has ever since deleted the mention of the Higg Index after facing a lawsuit.

Apart from that, the supply chains of the abovementioned fast fashion titans, together with luxury brands Prada, Adidas, and Nike, are responsible for cattle ranching for leather production, which has destroyed 80% of the Amazon rainforest.

Sadly, these statistics are projected to climb up by 2025 as the fashion industry will reportedly require 430 million cows every year to meet the demand for leather products.

What are the alternatives to fast fashion?

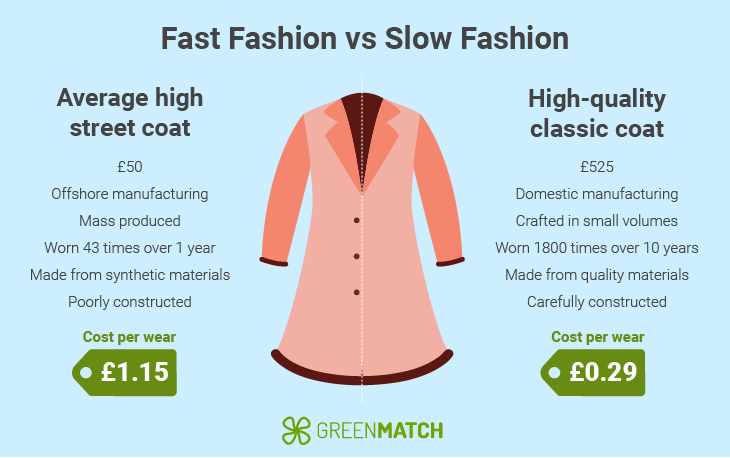

These environmental consequences of fast fashion are devastating and far-reaching. While the casual observer can't readily see and feel how fast fashion affects the environment, we can certainly witness how it affects our wallet and wardrobe.

Which changes in consumer behaviour and industry practices can we make to tackle this problem?

Slow fashion

The term "slow fashion" was coined in 2007 by Kate Fetcher, a design activist. She drew inspiration from the slow food movement, which started in Italy in the 1980s as a reaction to the rising popularity of fast food culture.

Slow fashion is meant to prioritise timeless design, durable materials, ethical production practices, and conscious consumption. The key is to find an approach that aligns with your values, budget, and lifestyle. How does one embrace the slow fashion principle?

"Buy less, choose well, make it last." – Vivienne Westwood.

Great representation of slow fashion principles, but what did Dame Vivienne mean exactly?

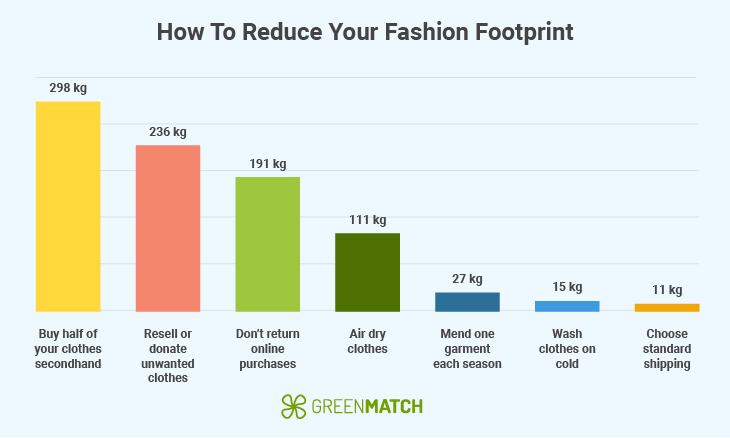

- Consider developing your own style and creating a wardrobe capsule with a basic list of garments needed to express it in everyday life. Carefully consider your purchases' colour, texture, and practicality, avoiding unnecessary clothing consumption. When you know that leopard print doesn't suit your style, you won't be as tempted to buy it, unlike those who follow fast trends. Moreover, according to the Waste and Resources Action Programme research, extending the life of clothes by just nine months can reduce their carbon footprint by 20-30%!

- Opt for clothes made from organic cotton, hemp, or Tencel lyocell instead of synthetic fibres. It ensures these items will break down easier and will lower your environmental impact. Look for reinforced seams and quality stitching that won't break easily. Prioritise investing in more expensive but more high-quality and, therefore, more durable clothing. Search for information about the fashion brand's sustainability policies and reputation before buying. Patagonia, Reformation, Everlane, KOHR, &Daughter, and Veja are among the most prominent sustainable slow fashion brands. These brands focus on timeless designs typically released twice a year. They use sustainable or recycled materials and have transparent supply chains. They also encourage their customers to repair and reuse their clothing.

- Make sure your wardrobe remains wearable for as long as possible. This means storing clothes properly, rotating them to prevent excessive wear, and choosing timeless pieces that don't go out of style easily. Apart from following washing and drying instructions, learn to fix and repurpose damaged clothes instead of discarding them.

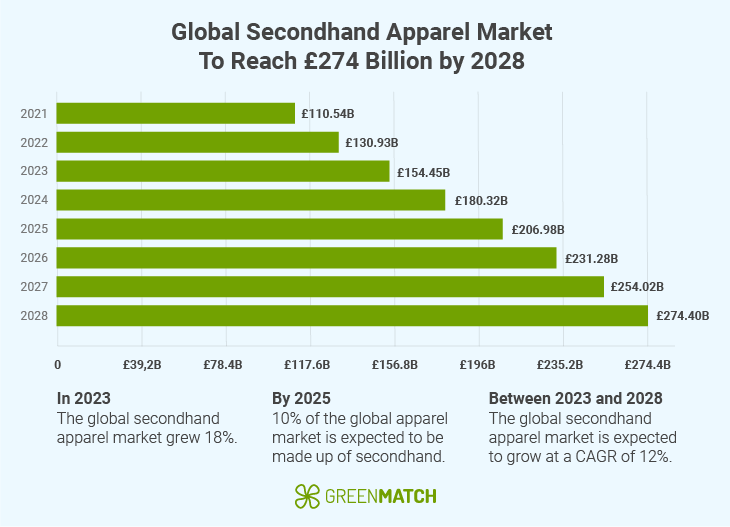

Secondhand shopping

While saving money remains the top reason to shop secondhand, 42% of US consumers visit thrift shops to achieve sustainability goals. The global second-hand market share is expected to reach $350 (£274) billion by 2028, with an estimated growth of 12% per annum.

Buying secondhand clothes extends their life and diverts them from ending up on landfills prematurely. Apart from reduced waste generation, shopping secondhand lowers CO2 emissions, too.

For example, Retail Dive found that if every consumer preferred a single secondhand piece of clothing to a new one, it would also save 87 billion litres of water as well as reduce CO2 emissions by over 2 billion pounds, which is equivalent to taking 76 million cars off the road for a day.

Eco-thrifting reduces the need for new production, which in turn lowers resource extraction and promotes a more circular economy in fashion.

Apart from the environmental benefits, secondhand shopping provides affordable fashion options for consumers on tight budgets and grants access to high-quality, brand-name items cheaper than their original prices.

Moreover, secondhand shops, especially vintage ones, offer unique pieces that aren't represented in mainstream fashion, which helps consumers curate their personal style.

DIY fashion and upcycling

Other sustainable and creative fast fashion alternatives are DIY fashion and upcycling. It encompasses modifying or transforming old or unwanted clothing into new pieces.

While it technically requires some tailoring skills and equipment, you can begin with basic projects like hemming and cropping, for example, turning old jeans into shorts or T-shirts into tote bags.

Invest in a sewing machine for more advanced projects or learn embroidery to personalise clothes. You could also adjust your old clothes with a tailor's help, which is still eco-friendlier than buying a new item.

Alternatively, you could donate excess and unnecessary clothing to charity, allowing others to use your garments in their own upcycling endeavours. Doing so can save 236kg (522 lbs) of carbon emissions each year.

Statistics and facts on fast fashion

- Fast-fashion workers in developing countries such as Pakistan earn as low as £54, compared to the demanded minimum wage of £163.68.

- The average fast fashion worker will most likely be paid about 4 cents (4 pennies) for a pair of $10 (£8) jeans.

- A polyester shirt produces 5.5kg of carbon dioxide, compared to 2.1kg from a cotton shirt.

- 51 countries use child labour within the fast fashion supply chain.

- The average workday of a garment worker is between 12 and 15 hours. SHEIN factory workers have 18-hour workdays with 1 day off per month.

- Less than 2% of garment workers make a living wage.

- 2013 saw the deadliest clothing accident in history when 1,132 workers were killed, and 2,500 were injured in Bangladesh during the collapse of the Rana Plaza garment factory due to structural failure and business owners' neglect.

- Clothing rental services like Rent the Runway and Mud Jeans offer sustainable alternatives to purchasing new clothes.

- Between 2000 and 2014, the amount of clothing produced exceeded 100 billion units per annum.

- SHEIN releases up to 60,000 new styles each month.

- 70% of fashion brands use Instagram to promote their production.

The future of fast fashion and necessary changes

As the well-known economic model states, demand generates supply. Therefore, as long as there's demand for inexpensive, trendy clothes, companies will continue offering low-quality, unsustainable items.

So, when discussing the future of fast fashion and ways to tackle its atrocious environmental consequences, we should address consumer behaviour and education. Here are key fast fashion trends and ways to shift consumer and companies' mindsets.

Accelerated production cycles

To capitalise on rapidly changing styles and meet consumer demand, the production speed of fast fashion brands has been reduced to 2-3 weeks.

For example, as opposed to 2 collections coming from clothes manufacturers in the 1980s, Zara currently has over 52 "micro-seasons" every year, with a new collection appearing every week.

Technology-driven trend prediction

Fast-fashion brands like SHEIN continuously use AI to analyse social media engagement, online searches, and purchase history. Machine learning algorithms identify emerging micro-trends and update the brand's 5,400 suppliers on new consumer preferences.

Suppliers immediately adjust their production processes and are ready to sell the new items as soon as 10 days.

Consumers should become more critical of trend-based marketing and make purchasing decisions based on their personal style rather than algorithmic suggestions. This could potentially slow production cycles and give brands room to use AI for supply chain optimisation, tracking environmental impacts or using the micro-trend data to implement recycling and upcycling.

Social media influence

With 3.5 billion monthly active users globally, Instagram and TikTok are at the forefront of trend propagation and distribution. 78% of consumers admit the influence of social media when making fashion purchases.

Influencer impact, TikTok viral challenges and hashtag trends propel fashion items into the spotlight and shape patterns and micro-trends and will continue doing so. The abovementioned platforms will introduce more seamless shopping options, which will allow users to buy directly from posts and videos.

Growing sustainability concerns

Since brands like H&M, Zara, Uniqlo, Mango, and ASOS are all slowly but surely implementing various environmentally friendly measures, we can conclude that they are driven by shifts in consumer behaviour. There's indeed a reason. 93% of eBay sellers state that sustainability is either "very" or "somewhat" important to them.

According to the same eBay report, 36% of Gen Zers, 39% of Millennials, and 26% of Boomers claim they "value sustainability and environmental benefits when buying pre-loved goods."

And over 40% of consumers are less likely to buy an item without a good resale value.

Brands will continue to focus on using recycled materials, eliminating toxic chemicals from production, and introducing measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Hopefully, fast fashion brands like H&M and Zara will succeed in their endeavours to launch garment collecting, recycling, repairing, resaling, and upcycling programs in the future.

Brands need to provide more transparency on their supply chains, for example, through blockchain technologies or AI and data analytics. These technologies should monitor environmental impact and track the products’ journey from production to sale, thus fostering consumer trust.

Rise of ultra-fast fashion

Currently, ultra-fast fashion is fueled by brands like Zara, which introduces new collections weekly, and companies like SHEIN and Temu, which sell clothes often as cheap as (or cheaper than) $5. Frequent turnover generates textile waste and exploitative labour practices to meet the "wear once" mentality.

This trend has no chance of stopping as Gen Z's purchasing power is growing. Since they are both trend-conscious and tech-savvy, they will likely fuel the demand for ultra-fast fashion. The competing brands will partner with micro-influencers to create limited-time collections and monetise on the hype-powered campaigns.

Consumer behaviour and regulatory measures. For example, in 2024, the EU adopted the Eco Design for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR). It aims to improve product circularity, set rules on carbon and environmental footprints, and strengthen legal compliance by implementing Digital Product Passports (DPP) for products and many more.

Conclusion

Which conclusion can we draw from this? Fast fashion is here to stay. However, both governments and brands continue introducing and adopting more and more measures to tackle the environmental and economic changes the industry has brought about. Yet, the main change depends on the end consumer.

When shoppers are educated enough about the harmful effects of careless, thoughtless, trend-based consumption, they will be able to drive systematic change in reducing the environmental challenges the industry causes.

By keeping consumers continuously informed, developing a circular economy and performing regulatory pressures, we might be able to transform the fast fashion concept into a model that prioritises speed and style without compromising environmental and social responsibility.

FAQ

Fast fashion is a business model that refers to cheap, low-quality replicas of catwalk and trendy styles that are made as quickly as possible.

Fast fashion accounts for 10% of global carbon emissions and 20% of industrial water pollution. It is also a reason for the growing levels of waste generation and environmental degradation and other concerns.

Recommerce, slow fashion, recycling, upcycling, mindful textile purchasing, and supporting sustainable fashion brands are considered to be the best alternatives to fast fashion.

Offshore manufacturing, cheap materials, low-quality, focus on micro-trends, and rapid turnaround from design to store are the most common traits of fast fashion brands. Some well-known representatives are Zara, H&M, Mango, SHEIN, Temu, Primark and others.

In 93% of cases, fast fashion worker’s wages don’t meet the minimum wage requirements. According to the independent investigations, SHEIN’s workers are paid 4 cents per item.

We strive to connect our customers with the right product and supplier. Would you like to be part of GreenMatch?